I.

In the introduction to his Faery Queen, Edmund Spenser makes a clever move, which is as curious as it is intriguing.

The prefatory piece is framed as a letter "TO THE RIGHT NOBLE AND VALOROUS

SIR WALTER RALEIGH, KNIGHT.

Lo: Wardein of the Stanneries, and her majesties lieutenaunt of the countie of Cornewayll."

The purpose of this dedication was multifold. For one, it was simply a literary convention at the time to offer such a deference. But Spenser also owed a debt to Sidney, their friendship connecting him to nobility, including royalty. (A second introduction is dedicated to the Queen.)

But there was more significance in doing this than mere decorum and chivalry. This introduction served as an opportunity for Spenser to explain his literary pursuit as one dedicated to the mythology of England, establishing himself as a representative of state and culture.

As Milton would with Paradise Lost, and as was common for educated persons of the age, Spenser looked back to ancient Greek authors for inspiration. In his depiction of King Arthur as "a brave knight, perfected in the twelve private morall vertues,” he is sure to stress that said number of twelve virtues was “as Aristotle hath devised." Not only was the King valorous — he was valorous in the manner of a Greek philosopher.

II.

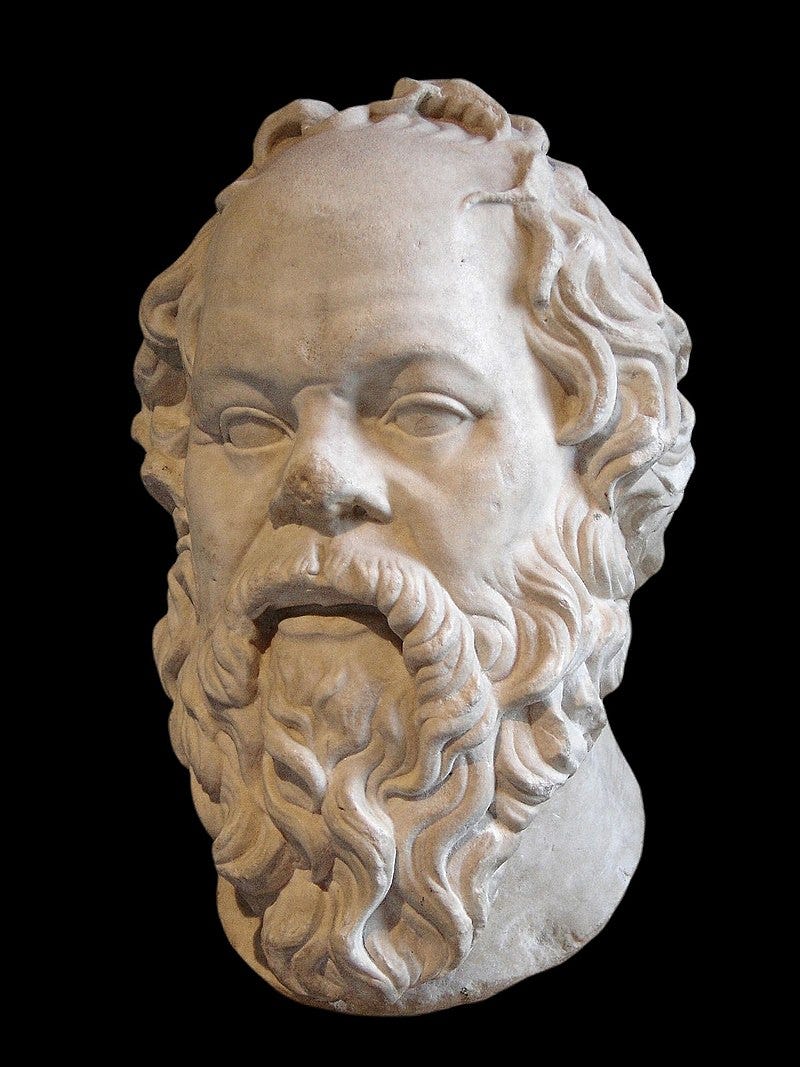

Of course, Aristotle was not the most famous of Greek philosophers (although he may well have been the most read). In fact, there was a more (in)famous philosopher who taught his teacher Plato (“the Wrestler with Broad Shoulders”). That sage educator was Socrates:

Socrates famously did not write. Instead, he taught by interacting via dialogue, sometimes giving advice, but more often asking provocative questions. Ultimately, these discourses would result in aporia, a place where a propositional truth can not be deduced. If done well, these states could emerge through friendly love, and serve as reward to interlocuter and conversant alike.

Spenser alludes to Socrates without naming him. He does this by instead referring to two philosopher historians, both of whom wrote accounts of Socrates.

Spenser describes the difference between the two as being one of political philosophy:

“Xenophon preferred before Plato, for that the one, in the exquisite depth of his judgement, formed a Commune-wealth, such as it should be; but the other, in the person of Cyrus and the Persians, fashioned a government, such as might best be”

To surmise, Spenser seems to be praising an early form of Liberal Socialism, more akin to Democracy than to Aristocracy (although this is curiously complex, and my understanding of Political History and Theory is so lacking that I do not feel remotely comfortable making any degree of claim concerning it).

III.

I do, however, feel comfortable talking about the different representations of Socrates which we find in Xenophon and Plato, if for no other reason than that Massimo Pigliucci has written eloquently about the differences in his new book The Quest for Character What the Story of Socrates and Alcibiades Teaches Us about Our Search for Good Leaders.

The book does much to show how Socrates went out of his way to challenge and educate those who would be potential statespersons. Pigliucci, an Italian-turned-American scholar who holds PhDs in both Evolutionary Biology and Philosophy, is able to boast that he attended Roman Catholic high school in Rome, translating Seneca from the Latin, and being steeped in arguably one of the best Humanities and Fine Arts educations available globally. Living skeptically as a United States citizen in an era where he worries greatly about our own capacity to enter into the type of Fascism under which his home nation suffered, he is a perfect authority to look at problems of political theory through the visage of Virtue Ethics, and uniquely suited to take a favorite among the two depictions of the Sage.

Incidentally, his choice is the same that Spenser makes. In a conversation with Donald J. Robertson about the book, Pigliucci states the following:

“For me the most interesting thing is that we tend to think of Socrates as he comes across in the Platonic dialogues — and for good reasons. A major source for what we know about him comes from Plato. But of course there are other sources, one important one which you know is Xenophon. Particularly the Memorabilia, which is also the book which inspired Zeno to get into Philosophy and start Stoicism. But in the Memorabilia you get, in my opinion at least, a far more dynamic, and interesting view of Socrates who talks to everybody about all sorts of things. So, in a sense, it's less philosophical and more practical. One of my favorite bits is where he actually enters into conversation with a courtesan and gives her business advice.

But, in terms of the discussion we're having, the more interesting thing in my mind is that Socrates apparently (according to Xenophon, at least) explicitly saw himself as playing this role of advising people whether to get into politics or not. And he does that repeatedly. First of all, there's a bit in the Memorabilia where a Sophist — Antiphon — actually criticizes Socrates for not getting into politics himself. And Socrates' response is ‘Well, how now, Antiphon — should I play a more important part in politics by engaging them in alone, or by taking pains to turn out as many competent politicians as possible?’ That's very revealing. And we have a number of examples. He advises Alcibiades not to do it -- so there is this point that's often brought up: ‘Oh, look at Socrates, he's failed with Alcibiades.’ Well, not exactly, because he did tell him not to do it! He told him don't get into politics, because he saw that it wasn't going to go very well. He also advises Glaucon, Plato's brother, not to get into politics. There's this really wonderful bit in the Memorabilia where Socrates basically does a very practical examination of Glaucon, asking him details about details about the Athenian garrison, and how much grain do we get, and all that sorts of stuff, and in the end he says ‘Please, don't do it.’ And Glaucon does not do it, and becomes a musician, apparently. And then Socrates advises Charmides. who was Glaucon's son, and this time he says ‘You are one of these people who *should* get into politics.’ [. . .]

So there is this pattern — it's not just Alcibiades. Socrates really thought of himself as kind of being on the outside and advising people whether to embark in a political career or not, and it's very interesting.

The theme seems to be that in the representation of Xenophon, we have a Socrates depicted in real terms — a sage who may well be wise beyond the capacity of all others, but who also highly values a sense of pragmatics in his consideration of Virtue. Hardly do we have a mythical person void of human characteristics.

Taking this into consideration, I can sense something peculiar about how Spenser has chosen to represent Arthur. Not only is he a proto-Republican of sorts, he is also a human being who perhaps earns his valor via his Character, as opposed to his blood line.

It’s a bold claim to make, and I’m no scholar on Spenser. But it certainly gets me excited to continue to shove on through his Faerie Queen. And imagining a parallel between a famous King and a philosopher who deliberately chose not to enter politics creates a sense of the dialogical in itself. “Such as it should be” rather than “as it might best be.” Ethics and character over theory and postulation. If it was forward-thinking for Spenser to think this way, it was extraordinary for Xenophon to have done so.

I wonder, centuries hence (if we make it that far), who among us might be so rendered.